Something I teach fledgling game designers is that building a playable world is different than building a comprehensive world—and you can get players invested in one much faster than the other.

Creating settings for roleplaying games requires a different approach than creating them for something like a comic or a movie. You don’t just want the world to feel expansive and lived in, but explorable and interactive, too. It may seem daunting, but to me what matters the most is identifying what the players are going to interact with most. Often that means people, places, and plot hooks.

“Every Thursday night, the Red Hooked Man stalks the streets of the Glassblowers District” is a sentence FULL of interact-able information for players. Players have a timeline (every Thursday night), a person (the Red Hooked Man), and a location (the Glassblowers District). Each gives them an avenue to confront this element of your setting. A good plot hook includes these elements, giving players plenty of opportunity to stumble into something interesting.

Let’s look at another example: “The king sent out his knights to find criminals in the city.” It technically has people, a place, and a plot hook, but it’s lacking an important spice: specificity! “The Felwinter King has sent his personal honor guard, led by Captain Morgaine, to cleanse the undercity of dust smugglers, making nightly transit between the districts difficult.” Suddenly your world is flooding with intrigue! Who’s the Felwinter King? Why is Captain Morgaine special? What’s dust and why does it have to be smuggled? I have no clue either, I just gave specific fancy names to vague boring things, but I’m excited to learn more alongside my fellow players.

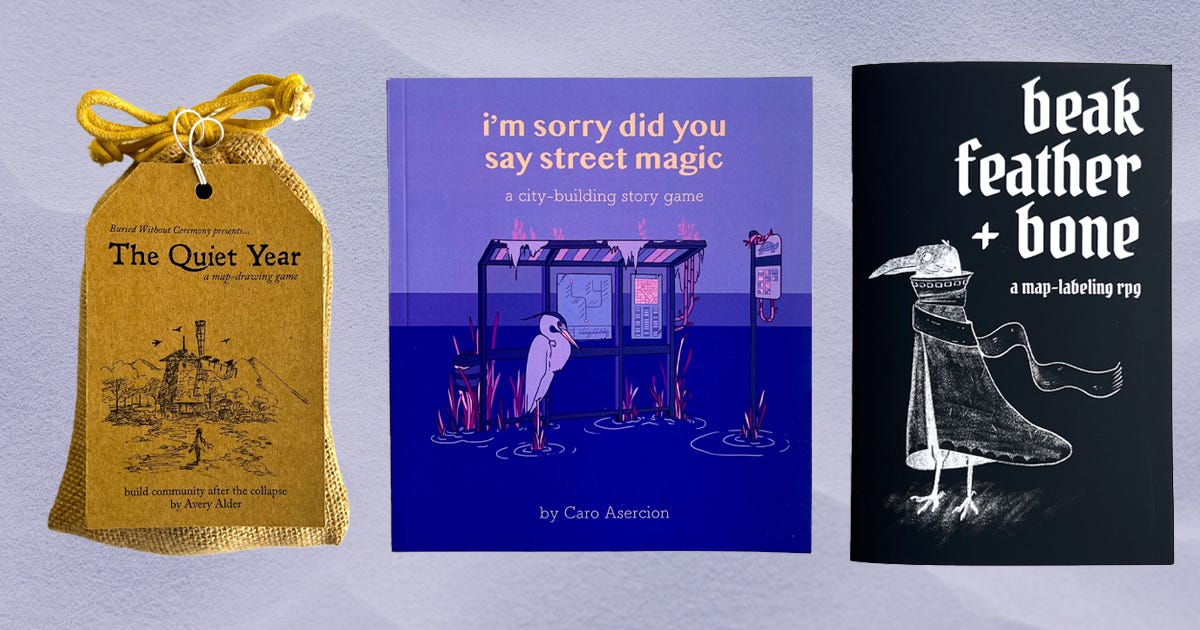

This is why I love playing and making worldbuilding games. They care about very specific things and get you excited to explore them collaboratively. The Quiet Year begins by asking you what resources are available to your community, but specifically what it cares about is what’s in Abundance and what’s in Scarcity. i’m sorry did you say street magic does not care about the spatial representation of your city but instead what places are related to each other and why they are important, big or small. Beak Feather & Bone, on the other hand, cares an awful lot about spatial representation, but specifically on an already existing map because it specifically cares about who owns what.

One of the things A Land Once Magic cares about is how the magic of the world changes the mundane. It cares about simple things, like transportation or communication, but invites you to get very specific about them. The prompt “Is there a common language? What is the common way to communicate long distances?” could be answered simply; “Yeah, everyone speaks Common.” or “We send letters via couriers.” But that’s boring and you’re not just answering the question in a vacuum, you’ve been thinking about a lot of specific, inspiring things prior to drawing that prompt.

A Land Once Magic starts by asking players to create a Palette of 3-4 descriptive words and a list of some inspirational Touchstones. You enter the world with specificity in mind. Our world isn’t just “science fantasy,” it’s “shattered, patient” and feels like “a 90s TMNT toy commercial.” Is just sending letters via couriers full of “radical turtle action?” No! Get more specific! If the magic in your world allows you to splice together aspects from different creatures, do dialects come about based on the local fauna? “Is there a common language?” is a question that will come into play because talking is something you tend to do in TTRPGs. Getting specific with such a mundane question lifts your world out of dull “the Elves speak Elvish” to “the people of Lynth vibrate at different frequencies to convey emotions like a cat would.” Now players have created a world that they can get real in the weeds about during play!

What’s the one fascinating detail that truly brought your most recent RPG world to life?

Making A Land Once Magic really taught me this. Originally, the game was mostly just a prompt table combining these specific and generic questions. Sure, enterprising worldbuilders could take “What common transportation method do caravans utilize?” into weird, specific territory but not everyone is willing to take the plunge. That’s why I have players start by creating A Legend. A specific story that is told in your world and is then, more specifically, warped into something else. You don’t just have a tale about an unbeatable monarch and personal sacrifice, you have a legend that leads to faith being born. Specificity implies time has passed, truths have been changed, and people use stories to further their own ideologies. Even more so, I included similarly over-the-top name suggestions for these elements. Your “unbeatable monarch” can be The Crimson Sword, Sol’s Lance, or the Vermillion Hammer. The Faith could call themselves Those Sacred Scorched, We Born of Blood, or Waders of Her Worldly Waters. Very rarely do people use these suggestions, but I’ve found that it encourages tables to just give things cool names!

So before you sit down to write your World Anvil bible, consider what exactly are your players going to interact with. And when you write down “The king sent out his knights to find criminals in the city,” stop! Get your table together to play a worldbuilding game and think about what specifically you all want to care about. Is a timeline of events important? Play Microscope! Is generational change in a place important? Play Grasping Nettles! Is a deeply flawed world crumbling around you important? Play Downfall! Is a unique magic system core to a world that is full of legends and stories important? Play A Land Once Magic! And within each game, decide together, who is the king? What’s special about the knights? Where are the criminals and what do they do? Get specific, get invested, make a playable world.

— Viditya Voleti, designer of A Lance Once Magic, Bloodbeam Badlands, Space Between Stars, and more

Time Force RPG: Trip Through Time to Save the World

Back it Before Time Runs Out!!

Our good friends at Mythworks (The Wildsea, Slugblaster) are in the final hours of their crowdfunding campaign for Time Force, a one-shot zine game about a nonsensical journey through time to stop an impending apocalypse!

Mechanically similar to Honey Heist or Blades in the Dark, Time Force is quick to pick up making it easy to dive into your time-travelling story almost immediately. Plus, a unique ripple mechanic enables players to explore how their actions affect their own futures.

Watch it played in a great actual play run by Graham Gentz (Creator of Under the Autumn Strangely)

Mythworks creates some of the best games on the market and we love everything they do to support the independent tabletop community. So go check out Time Force RPG and back this project to help them cross the finish line on their Kickstarter in style!

🗞️ News Worthy

Shadowdark RPG: The Western Reaches raises over $1 Million on first day of crowdfunding.

The Changing Face of the Tabletop Industry’s Trade Association (Rascal)

Yazeba’s Bed & Breakfast is a finalist for the 2024 Nebula Award for Best Game Writing. [Listen to our Yazeba’s Series]

🎲 What We’re Bringing to The Table

🎥 Watch: Where Can Shadowdark Go From Here? by Questing Beast

📚 Read: What is a Core Game Loop? by Skeleton Code Machine

🎧 Listen: Yes Indie’d | Post Fantasy Worlds (w/ Viditya Voleti)

🎙️ New From The Studio

Talk of the Table with Viditya Voleti (Monday, March 17)

Bitcherton Episode 10 with Aabria Iyengar (Wednesday, March 19)

My First Dungeon presents A Land Once Magic (Thursday, March 20)